Loading...

Home > Newsletters > May 1, 2023 > Out of sight, out of mind: How financial intermediaries obscure accountability for community harm

May 1, 2023

Out of sight, out of mind: How financial intermediaries obscure accountability for community harm

Various transparency and accountability challenges arise when development finance institutions use financial intermediaries, such as national and regional banks, without proper safeguards.

Certain Development Finance Institutions (DFIs), such as the International Finance Corporation (IFC) of the World Bank, seek to achieve their stated aim of reducing poverty and increasing shared prosperity in developing countries by providing financing to the private sector.

However, rather than infrastructure or energy, the sector that receives the largest portion of IFC financing is the financial sector itself – essentially national and regional banks, private equity and hedge funds – which can then on-lend that money. These are commonly referred to as financial intermediaries (FIs).

This article delves into what happens when money is outsourced into the private financial sector through financial intermediaries, where transparency and accountability frameworks are weak, and examines how that affects communities’ access to remedy.

Financial Intermediaries (FIs)

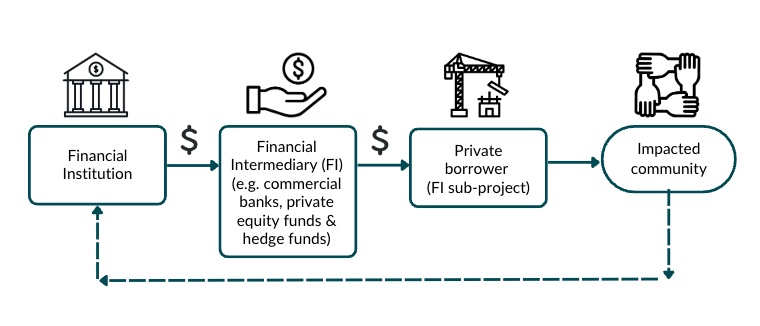

In simple terms, financial intermediaries (FIs) act as middlemen between financial institutions and private companies seeking investment. Examples of FIs include commercial banks, private equity funds and hedge funds.

The use of FIs by DFIs has increased over time. The IFC invested $15.5 billion in FIs between 2010 and 2013. Between 2010 and 2016, its investment in FIs rose by 45%, with the IFC committing $23.9 billion to FIs between 2015 and 2018. Now, more than half of the IFC’s portfolio is invested in FIs, that are then on-lent to borrowers (FI sub-projects) with limited to no oversight. Other development banks have followed suit in using FIs.

The IFC argues that using FIs improves its access to financial markets in developing countries, allowing it to support more micro, small and medium enterprises than it would be able to on its own, therefore expanding its impact and reach. However, there is evidence that much of the IFC’s investments in FIs do not actually go to small businesses, but rather to large corporations that own and operate major high-risk investment projects: without the level of environmental and social due diligence that would be required if the IFC was investing in those projects directly. Evaluations by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the African Development Bank (AfDB) also both independently found that:

“Projects implemented through financial intermediaries have remained the weakest performers on safeguards” (UN OHCHR, Remedy in Development Finance, Page 15).

In addition to the increased risk of non-compliance with environmental and social standards, the use of FIs by financial institutions raises issues of a lack of transparency and remedy for communities harmed by FI sub-projects.

Lack of Transparency

One issue that arises when using FIs is the lack of transparency, mainly the difficulty of tracking the flow of funding through FIs to sub-projects without enhanced disclosure from FIs or DFIs.

Hidden Investments in Lamu Coal-Fired Power Plant

This issue can be seen in the complaint against a proposed 1,050 megawatt coal-fired power plant project in Lamu County, Kenya.

In 2014, private developer Amu Power was awarded development rights to build and operate this coal plant on the idyllic coastline of Lamu. This project was met with resistance from local communities, recognizing the devastating environmental, human rights, and cultural impact of the proposed coal plant. Despite the significant risks, project developers failed to meaningfully consult affected people and did not genuinely respond to their concerns.

On April 26, 2019, two community groups filed a complaint with the IFC’s accountability office, the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO). With the help of international organizations including Accountability Counsel, the groups tracked the complicated investment chain for this project through the financial statements of Centum Investment, the majority shareholder of Amu power, the coal plant’s developer.

Despite having pledged to avoid new investments in coal projects, the investment chain indicated that the IFC was financially exposed to the coal plant project through financial intermediaries, including the Co-operative Bank of Kenya, Kenya Commercial Bank, and the FirstRand Bank of South Africa. Each of these banks, which received funds from the IFC, provided loans and/or credit facilities to Centum Investment.

Figure 1 - Source: CAO Complaint, page 17. After the complaint was filed, a further investment by IFC in FirstRand Bank of South Africa was linked to the project companies.

The Lamu Coal-Fired Power Plant complaint was found ineligible by the CAO for technical reasons, including the fact that the IFC’s investment in FirstRand Bank – which was never explicitly disclosed on the IFC’s project information portal – was repaid shortly before the complaint was filed, without any public notification. Despite the glaring lack of accountability for IFC’s contribution to the project, the coal plant proposal fortunately did not proceed after facing both financing and licensing issues.

Transparency Challenges

Various transparency issues were highlighted in this complaint, including:

- A lack of transparency around the existence of the investments (due to a lack of explicit disclosure).

- A lack of transparency around how the funds were being used by IFC clients and the use of sometimes illusory “ring-fencing”.

- A lack of transparency around the CAO’s decision-making for FI complaints.

These transparency issues, often combined with complex corporate structures, financial transactions, and bank secrecy laws, create challenges for local communities trying to track who is ultimately responsible for harmful projects, what protections they are entitled to, and how they can seek remedy.

The impact of this lack of transparency on accountability can be seen clearly in the data gathered on the Console, which as of April 2023 lists only 20 out of 337 IFC/MIGA complaints as complaints relating to FI investments. Given more than half of the IFC’s portfolio is now invested in FIs, it stands to reason that the lack of transparency associated with FI investments is severely impacting accountability.

While extremely limited, the data we have shows the majority of complaints about FI sub-projects (63%) have produced a dispute resolution agreement or a publicly disclosed compliance report (66% of which have found non-compliance). A majority of these FI-related complaints relate to loss of livelihood (60%) and physical and/or economic displacement (60%).

Commitment to Increased Transparency

Some DFIs have begun to implement reforms in this area. The IFC, for example, made a commitment in 2020 to improve transparency by mandating its FI clients to report annually on the details of sub-projects funded through high risk loans. Despite this fact, the transparency of DFI investments in financial intermediaries remains low:

“Core information for FIs was generally available, although reported inconsistently. Disclosure of FI sub-investments was significantly lower than at the FI level and was limited to investments by private equity funds.” (Publish What You Fund, Advancing DFI Transparency, page 5)

The IFC did not start publishing disclosures until recently. Christian Donaldson, Policy Advisor at Oxfam, emphasized the need for further improvement, pointing out that the IFC has only disclosed information on 10 FI investments,* with only one of these investments disclosing information on its FI sub-projects.**

Bridging this transparency gap, a coalition of civil society organizations took on the responsibility of tracking the flow of funds between 2017-2020 through 318 FIs in a FI sub-project database. However, this burden should not fall on civil society organizations to invest their limited resources into tracking this information. Access to this data should be considered a fundamental right, and both DFIs and their FI clients must commit to disclosing sub-project level information.

IAMs must also prioritize transparency by publishing details of ineligible complaints on their complaint registers. Since the Lamu complaint was found ineligible, and the CAO does not publish details of ineligible complaints on its complaint registry, the only mention of this case by the CAO is on page 2 of its FY2019 Annual Report which simply notes the presence of “12 ineligible cases” for that year. Due to the lack of information provided by the CAO, these unknown, ineligible cases are listed on the Console as such. All the data we have on the Lamu complaint is a result of Accountability Counsel’s involvement in it; by not publishing details of all complaints on its complaint registry, IAMs are further limiting transparency and accountability.

Lack of Remedy

In the rare cases where a harmed community is able to track an investment and successfully make a complaint against an FI sub-project, the question of who is responsible for remedy arises.

Harm Caused by Barillas Hydroelectric Dam

In 2008, the IFC provided $20 million in loans and $10 million in equity to the US-based Inter-American Infrastructure Finance Corporation (CIFI). CIFI, acting as the financial intermediary, then provided a loan and mezzanine facility to Hidro Santa Cruz, S.A. (HSC), a subsidiary of Spanish company Hidralia, to fund their infrastructure project in Santa Cruz Barillas, Guatemala.

HSC bought land in the area to construct a hydroelectric dam, but failed to engage with the predominantly indigenous Mayan population in the area. This led to distrust and opposition amongst the community, which escalated into a cycle of community protests, violent crackdowns, arrest of local activists, and kidnappings. In July 2015, a group of community representatives filed a complaint with the CAO regarding this project. Following the complaint being filed, financial backers pulled their investments, and then HSC announced the termination of the project.

The CAO continued to investigate this complaint and released a compliance investigation report in December 2018 that found the IFC negligent in preventing harm to Indigenous communities. The CAO concluded that:

“Though aware of project impacts during the period of financing, IFC did not engage with its client to ensure that residual impacts of the project were assessed, reduced, mitigated, or compensated for, as appropriate, including at project closure, as required by the Performance Standards and the Sustainability Policy.

In these circumstances, contrary to the intent of IFC’s Sustainability Policy, adverse impacts have been left to fall on the community” (CAO, Compliance Investigation Report, Page 52).

In response, the IFC acknowledged the harm suffered by the community and admitted to some failures in conducting adequate due diligence and monitoring. However, despite investing in the project and acknowledging its shortcomings, the IFC has so far refused to remedy the harm caused to the community.

IFC/MIGA External Review

In 2020, an external review of IFC/MIGA identified that the IFC’s investments in financial intermediaries were inadequately governed. The Review found that the IFC had significant gaps in ensuring that its FI clients properly assessed environmental and social risks. The Review also found that the complexity associated with FIs also made it challenging for affected stakeholders to access the CAO, and for the CAO to determine if complaints were eligible.

The Review recommended that the IFC improve its supervision, due diligence, and transparency when it comes to FI clients and FI sub-projects. The Review also specifically highlighted the necessity of improving the systems for providing remedy to affected people. It found:

“[M]ost CAO non-compliance findings do not lead to effective remedy. [...] Data show that in the vast majority of cases, IFC responses to address project-level compliance findings are insufficient and/or ineffective” (at [311]).

The Review recommended that the IFC/MIGA and its clients should directly contribute to remedy where their investments contribute to harm (including in the form of financial compensation). Where a client causes harm, the IFC/MIGA should exercise its leverage to prompt remedial action by its clients, and establish a source of contingent liability funding for every project, thereby creating a means of funding remedy.

The Review noted that the responsibility to contribute to remedy should not be limited to the time period when an active financial relationship exists between IFC/MIGA and its client, as complainants “may not become aware of the link between harm and IFC/MIGA involvement until after the financial relationship has ended (especially if IFC/MIGA funding was channeled through a financial intermediary).”

OHCHR Remedy Report

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) released a 2022 report highlighting the need for DFIs to center the rights of people in their investments and facilitate the right to remedy. The report showed that many communities that have been harmed by DFI-funded projects never obtained remedy.

IFC/MIGA Remedy and Responsible Exit

In February 2023, the IFC released a draft of its remedy framework, Approach to Remedial Action. Despite the data in the Console painting a grim picture of the IFC’s approach to remedy, the draft Approach has not provided a comprehensive plan for delivering remedy to affected communities. In the Approach, the IFC heralds its existing prevention and mitigation practices, and does not provide a framework where the IFC and its clients must contribute to remedy when they contribute to harm.

Moreover, despite the fact that FI clients now make more than half of the IFC’s overall lending portfolio and the fact that the IFC has struggled to ensure its FI clients apply its environmental and social standards or provide remedy when communities are harmed by FI sub-projects, the draft Approach surprisingly makes little to no mention of FIs.

The Approach fails to meet the recommendations provided in its own Review, only noting that “relevant elements” of the Approach (particularly those related to client preparedness) would apply to FI transactions. However, the IFC did not use this opportunity to clarify how it would ensure the environmental and social performance of its FIs, strengthen its supervision and due diligence of FI clients, nor enhance the transparency of FI sub-projects.

Further, not only does the Approach not create a means of funding remedy, by either the IFC/MIGA or FI clients, it even goes as far as stipulating:

“For the avoidance of doubt IFC/MIGA will not require FI clients to establish their own Approach equivalents.” (IFC/MIGA, Approach to Remedial Action, Page 13)

The Approach misses the chance to define roles and responsibilities of FIs in relation to remedy, and does not provide any framework that holds itself and FI clients accountable for their contribution to harm.

It is imperative that the IFC adheres to the recommendations of its external review and the OHCHR report to ensure that its remedy framework strengthens its ability to monitor its FI clients’ compliance with IFC standards and provide funding where its sub-projects cause harm to local communities. Similarly, the IFC’s Draft Responsible Exit Principles should expressly commit to not exit projects without remediating harm first, or not exit projects that have ongoing CAO cases without the consent of the community complainants.

This is crucial to ensure development financing benefits communities, and accountability is not obstructed for those adversely affected by development finance.

A call for reform in the use of FIs

The cases mentioned above shed light on the transparency and accountability problems that are common with the use of financial intermediaries in the development sector. The lack of disclosure and transparency in financial flows, leads to complex webs of intermediaries that local communities have to navigate, providing challenges in figuring out responsibility for harm. Furthermore, the absence of a requirement for FIs to fund remedy, and the lack of commitment from DFIs to provide remedy directly to affected communities, leave many communities without effective solutions when harmed by FI sub-projects. Thus, reform is necessary to address these issues and ensure greater accountability and transparency in the use of FIs.

* To access IFC Financial Intermediary investment disclosures, refine by: “Financial Intermediary Disclosures” in the left navigation bar of the search page.

** To access IFC Financial Intermediary sub-project disclosures, click into an investment disclosure (for example: ABSA Bank Limited), then click into the “E&S Category Rationale / Risks and Mitigation” towards the bottom of the page, then: “Financial Intermediary Sub-Project Disclosure”.

Tags: Best Practices, Community Harm, Financial Intermediaries, Remedy, Responsible Exit, Transparency