Loading...

Home > Newsletters > March 4, 2025 > Against the wind: Resistance, rights, and reckoning in Mexico's Isthmus

March 4, 2025

Against the wind: Resistance, rights, and reckoning in Mexico's Isthmus

This post is a personal reflection tracing the long-term impact of a 2012 complaint against a major wind farm project, examining both its institutional legacy and its effects on local communities in Mexico's Isthmus of Tehuantepec.

Twelve years ago, a formal complaint contributed to stopping what would have been Latin America's largest wind farm in Mexico's Isthmus of Tehuantepec (“the Isthmus”). The complaint led to new documentation and protocols at the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). Yet when I arrived in the Isthmus this summer, I discovered something surprising: while everyone had strong opinions about wind farms, almost no one knew about the formal complaint. This investigation explores what that disconnect reveals about accountability in renewable energy development.

The timing of this investigation feels urgent. In February, Mexican president Claudia Sheinbaum revealed an “energy overhaul” that effectively reopens the country to international investment, fueling expectations that renewable energy projects may restart after years of stagnancy under the Lopez Obrador administration. As communities worldwide file complaints on similar projects through Independent Accountability Mechanisms (IAMs), the lessons from this case could shape how we approach the renewable energy transition ahead.

Background

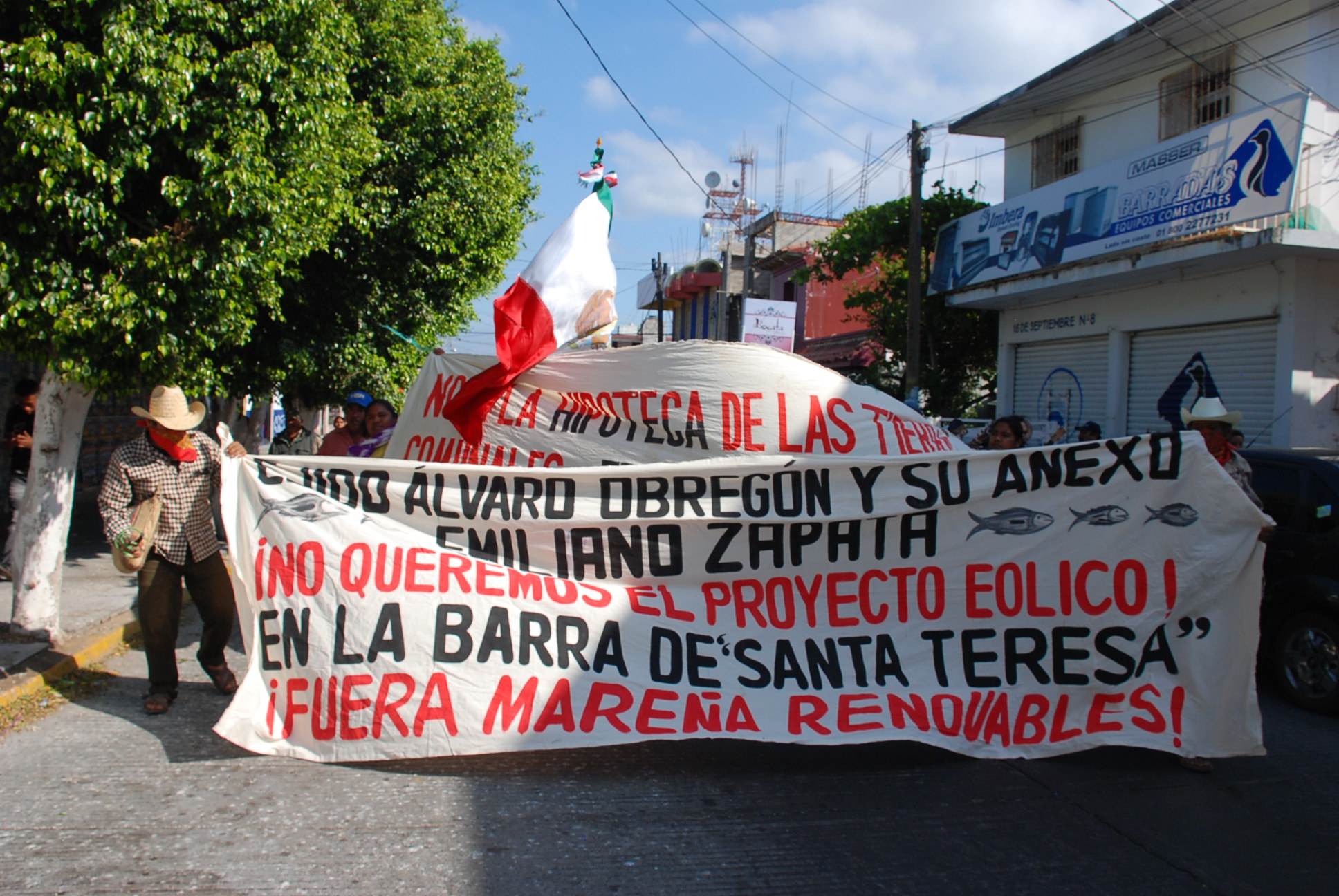

Image source: Desinformemonos

In the world of international development, a number of renewable energy projects have been the target of community complaints—which are often handled by IAMs. One of the most notorious among these is the 2012 Mareña Renovables wind farm complaint in the Isthmus. I traveled there to understand its legacy, to trace what happens after the paperwork is filed and the media attention fades.

The Mareña case immediately caught my attention for its scale and controversy: developers had planned to build Latin America's largest wind farm—a 396 megawatt facility— atop local fishing grounds and an indigenous sacred site.

The project's location in the Isthmus’ Laguna Superior made sense from a business development perspective. The area's unique geography boasts some of the strongest and most consistent wind resources globally, and since the early 2000s, wind farm developers had been steadily establishing projects across the region, securing land at remarkably low prices, as local landowners were initially unaware of the valuable resource literally blowing across their fields.

The Mareña project consultation revealed a total disconnection from the cultural context, and led to accusations of backdoor deals and bribery. These missteps, among others, caused the project to start unraveling. Among mounting tensions, affected community members filed a complaint to MICI, the IDB's IAM. Ultimately, the attempt to construct the wind farm sparked regional unrest, leading to protests, threats, and tragically, two deaths — and the project was eventually canceled and relocated.

What the paper trail revealed

Before heading to the field, I looked through the publicly available information online. The official complaint documentation tells a story of institutional learning: the IAM acknowledged policy violations in indigenous consultation, information disclosure, and environmental safeguards in its compliance report.

Compliance report findings and commitments:

| Policy | Findings | Commitments |

| Environment and Safeguards Compliance Policy (OP-703) |

|

|

| Access to Information Policy (OP-102) |

|

|

| Indigenous Peoples Policy (OP-765) |

|

|

The IAM published a one-pager summarizing the lessons learned from this case, and the bank produced new guidance documents, training programs, and consultation protocols. The public can even access some of these outputs, like project documents and the Meaningful Stakeholder Consultation note that emerged directly from this case.

But what actually changed on the ground?

To find answers, I headed to Juchitan de Zaragoza, a city in the middle of the Isthmus for the summer to get to know the area and study the local Zapotec language. What I discovered revealed that this wasn't just about one wind farm — it was one part of a much bigger story.

The wind farms reveal themselves

I arrived in Juchitan, my home for six weeks, to the city’s sticky heat and humidity, its relentless sun, sudden downpours, and massive trees filled with hundreds of screeching black birds (bigose yaase’). Buildings were covered in murals with words in Zapotec, and the large central market filled with regional dishes like the typical tortilla (guetabiguii), dried shrimp (benda buaa’), and shrimp cakes (guetabingui).

I also noticed: there were no wind farms in sight.

It wasn’t until several weeks later, leaving town for the neighboring town of Union Hidalgo, that I saw wind turbines lining the entire route. Stepping off the bus, my jaw probably dropped a bit — a turbine was visible from Union Hidalgo’s town center, its blades rotating like a giant greeting. Wind farms surrounded farmhouses, lined roads, and encircled the next town too. Standing roadside, they sounded like a massive swarm of bees, loud and ominous.

My Zapotec professor was well-connected, and I spent the weeks slowly getting to know more of the Zapotec (binnizá) and Huave (ikoot/ikojts/konajts) local communities. I learned about the complicated and challenging relationships amongst groups. And soon, I was introduced to the anti-wind farm activists, or “anti-eolicos”. They took me to see different parts of the communal land, bienes comunales. One of our destinations was a hill overlooking the region. At the top, I took in the view: hundreds of wind turbines stretched to the horizon. The tropical savanna looked like it had received acupuncture treatment—white toothpicks transforming the flat, scrubby landscape. I finally understood: wind farms had taken over much of the Isthmus.

Looking out over the horizon, I heard one anti-eolico’s words echo: "When will they stop? Only once every inch of the Isthmus is covered in wind farms?"

Relocation, not resolution

The resistance to Mareña fit within a broader pattern of renewable energy development and contestation in the Isthmus.

After the sandbar project's cancellation, developers reconstituted it as Energia Eolica del Sur (EES) several miles away—the same wind farm I'd first seen from Juchitan. While EES was subjected to Mexico's first official Indigenous consultation process — to obtain FPIC (Free, Prior, and Informed Consent) — in 2014-2015, academic research raises concerns about the procedure. Research documented irregularities: participants faced systematic intimidation, the technical committee failed to address dozens of community concerns about environmental and social impacts, and project information was withheld. One local resident I spoke with confirmed these findings, describing his personal experience: he attempted to participate in consultations but ultimately abandoned the effort upon receiving repeated threats. Although the project received official approval in mid-2015, community opposition secured a temporary court injunction, supported by over a thousand local signatures, though this legal victory proved short-lived.

In the years since, the pattern of contested development has evolved. In 2020, Union Hidalgo residents leveraged France's duty of vigilance law, a law making large corporations responsible for preventing severe human rights impacts in their supply chains, to challenge an EDF wind farm. Yet this project-by-project resistance places the burden on individual communities to repeatedly challenge new developments rather than addressing underlying systemic issues.

Layers of context

The Mareña Renovables conflict revealed deep complexities in the Isthmus region. Through conversations with locals and activists, I started to understand how historical forces shaped both the wind farm's development and its resistance:

- Changes in national policy drove wind farm development. Mexico's energy policies first restricted private generation to the national supplier (CFE), but regulatory changes in the late 1990s and the Peña Nieto administration's reforms created openings that accelerated wind development.

- The region's complex indigenous history complicated unified resistance. Zapotec dominance over ikoot/ikojts/konajt and Zoque peoples created lasting tensions, which contributed initially to preventing unified resistance against the wind farms.

- The developers' approach revealed a profound misunderstanding of this context. Their "consultations" focused on legal compliance rather than meaningful dialogue, exemplified by English-language presentations in communities where even Spanish wasn't primary, and sending Zapotec translators to Huave communities.

- Community benefits remained ambiguous. What I saw in the Isthmus didn’t convince me that the wind farms had benefitted the region’s “development”. The energy generated from Mareña would have gone to a beer company owned by Heineken and FEMSA, a large Mexican multinational consumer company—not residents. And although the EES social benefits commitment showed promise—l was told it funded a successful Zapotec language program— impact was limited by the one-time nature of project funding. Technical maintenance jobs typically went to outside specialists, construction work was short-term, and land rental payments benefited only certain landholders.

These contextual factors were not obvious looking at complaint documents, but became clear through spending time in the region, talking with people. By living there, I witnessed how indigenous culture and language permeated daily life—making the developers' cultural oversights particularly striking.

Tracing the complaint’s legacy

Given the scale of regional unrest and the complaint's role in this contentious history, I expected to find its legacy clearly etched in local memory. Yet when I arrived in town seeking people to discuss the complaint, I discovered something surprising: most residents didn't know about it. Everyone had strong opinions about wind farms—but finding people who knew about the formal complaint processes for international investors proved elusive.

I eventually managed to speak with several people involved in filing the complaint.

I spoke with an ikojts resident from San Dionisio who had led the effort to file the original complaint. He told me how he was so desperate to have someone listen to his concerns, that he went to Mexico City’s Zocalo central plaza to plead to the public. There he connected with protesters at the Monument to the Revolution, who linked him with Luz y Fuerza, a large activist group. They helped organize a press conference, and another organization guided him to MICI. In this way, he filed the oft-overlooked first complaint against the project — which was effectively dismissed by the mechanism with little explanation.

The second complaint, which generated the well-documented outputs, was submitted in large part due to the efforts of the Assembly of Indigenous Peoples of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in Defense of Land and Territory (APIITDTT). The group mobilized regional support and funds to file with the professional help of the Indian Law Resource Center. After successfully connecting with the Center's international legal team to file the complaint, they hadn't filed another since. I asked why not. "I'm tired," explained my contact, referencing the extensive efforts and resources required to navigate the process.

The ikojts resident is tired, too. He has since left the Isthmus to manage ongoing health issues. He told me he doubted he'd reach age 55, and recounted the toll of years of constant threats, including a near-death encounter during the resistance movement.

Overall, my visit to the Isthmus raised more questions than it gave answers about the role of the complaint in the whole resistance movement. But I am left with several lingering observations of the complaint’s legacy:

- When faced with organized resistance and the formal complaint at the original project site, IDB and developers relocated the project. Though they undertook a formal consultation process at the new site for EES, reports suggest it may have fallen short of meaningful FPIC standards. The project that emerged displayed many of the same issues that sparked the original resistance, suggesting the limits of institutional learning from this case. Overall, this finding highlights the persistent challenges communities face in asserting their right to FPIC, and the comparative ease with which corporations can sidestep meaningful implementation.

- The complaint plays a surprisingly minor role in local memory of the resistance. The complaint was one part of a larger resistance movement and regional history. Despite its apparent importance institutionally for the IAM, I had to actively search to find anyone, even among activists, who knew about or engaged with the formal complaint process. Ultimately it took the involvement of a small number of well-organized, -educated, and -resourced individuals to successfully navigate the complaint process.

- A complex socioenvironmental and political context shaped the complaint. This project sat at the intersection of international finance, energy policy, local/state/national political interests, and resistance networks shaped by historical group relations. This intricate context must inform how the complaint's impacts get interpreted—particularly important given that most IAM research takes a broad international view, with limited empirical evidence of how complaints function on the ground and intersect with national politics.

- We cannot reduce the complaint's impact to a simple narrative of "the complaint stopped the project”. Because it didn't. As I continue this research, I aim to understand its more nuanced effects: the symbolic, material, and personal impacts at both community and organizational levels, which will likely reflect back on the political and social context described above.

Stepping back and looking forward

These findings—about the complaint's limited local footprint, its complex context, and its nuanced impacts—point to important questions about the future of renewable energy development and accountability. A single complaint's story can highlight challenges that might be otherwise missed.

Wind farms correspond to widespread impacts on local communities. We can see that globally, wind farms have generated 16 complaints over the last decade — in geographically diverse locations including Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas.

*Note: data from 2023 is incomplete

This matters because we are, and will likely continue to see, an increase in renewable energy projects around the world. Based on the International Energy Agency's 2024 data, global renewable energy capacity could grow by 150% from current levels by 2030.

It’s imperative we learn from past complaints as complaints against wind farms persist, and questions linger about the future role of IAMs and the broader commitment to accountability among project financers. Regardless of how accountability mechanisms evolve, lessons from cases like Mareña Renovables—about consultation, community engagement, and the complex interplay of local and global forces—will remain important. By examining these stories closely, we can better understand how to pursue both climate solutions and environmental justice in the renewable energy transition ahead.

Tags: Research